Last month I earned 44 cents through playback streaming of my music on Rhapsody. It doesn’t sound like a whole heap of beans, does it? I mean, what can you buy for 44 cents? I don’t know. But anyway, I am not a professional musician here to whinge about how terrible my life is and how I hate flying around the world performing my music to gullible fans who are willing to throw their money at me. I am not here to complain about how my management team stiffed me as I sit by my swimming pool at my apartment building in Santa Monica. I am not going to complain about how the royalty rates of digital downloads are terrible as I sniff a line of cocaine from the smoothly shaven cleft of a $2000-a-night hooker.

No, I am just some chancer who makes tunes on his own. It still amazes me that I can actually make a little bit of money out of the music I produce. I mean, would you actually pay to listen to this crap? I wouldn’t – but then I make it and I listen to it an awful lot as I mix it and get it ready for human consumption. It costs me about £40 in total to get my music “out there”. My production costs are my gear, which I’ve amassed over the years, but probably totals a couple of grand, and little else. Anyone can make music that is saleable for next-to-no-cost. It is the punk ethic made real, but this time instead of attitude and a sneer, you can actually record real tunes that everyone can whistle.

Let’s face it, the music biz has had it cushy for a long, long time. It’s a very young industry in comparison to say the world of fashion or any of the other arts. The guys at the top made a lot of money very quickly and this has been at the exploitation of the majority of musicians. Only a handful of the crop “make it” and actually walk away with a handsome share of their royalties and the ownership to their own intellectual property.

In ye olde days the story went like this. Band gets spotted by A&R man, they are offered a contract with an advance that covers them buying musical instruments, recording an album or single, making an accompanying single and a promotional budget for said works. So before a note of music has been recorded, the band is in debt and owes the record company their advance back. You could say that the record company is gambling – like the horse races – on which group is going to be the next big thing. But they are in a win-win situatio because despite them paying an advance, it will be the band who pays the tab – and then some!

The band records the single, racks up studio time, pays for an expensive video and spends money on an entourage it cannot support. This all comes out of the advance. The single is a hit, but by the time the management team take their cut and the band gets theirs, there’s still a substantial part of the advance left to pay. So they then have to get on the live circuit and earn some cash to pay back their paymasters. If they have a hit in the meantime, everything is fine, everything gets paid off until the next time it comes around to make product.

Those musicians without a savvy financial flare would soon find themselves in debt as the hits dried out or their spending (usually encouraged by the record label) broke the bank. The Michael Jackson story is a good illustration of this where his spending was bankrolled by Sony Records on the hope that he’d go bust and they’d get their hands on the Beatles back catalogue as collaterol. Yes, the music biz is that cynical. However, Jacko foxed them all by dying and earning more money than Scrooge McDuck plus Alan Sugar squared by Donald Trump and multiplied by Bill Gates. Sony huffs off in a mood, paid off and no nearer to acquiring that valuable back catalogue.

Of course, for most bands on the wrong end of a music deal, being broke meant that they probably signed over their copyright to the record company, allowing said company to profit from any further releases of that material, whether it be re-releases, movie soundtrack usage or compilation fodder. It really is a business that’s win-win – there is little or no risk involved.

So in the old days, to be a musician would mean certain debt – thrust upon you by those who invariably entrusted your career with. It’s those relics of that bygone age that moan and whinge about downloading killing music and try to undermine the current legitimate downloading and streaming services by pointing out how low the royalty rate is.

Back in the days when Dave Lee Travis was the Hairy Cornflake, there was this thing called radio. It was a strange concept. I can only describe it as a little box with a dial that played music. Yes, free music. You didn’t have to pay for it. You just paid for the box and the music that came out was free. OK, there was this strange thing called the radio licence, but it was the same as buying a licence for your dog in those days – only the stupidly honest actually did it.

But radio was a marvellous thing. You could listen to the top tunes of the day and if you didn’t like the current song, you could move the dial and the music would change. If you didn’t have any money, but liked the hits of the day, you could tune in for the Top 40 pop parade run down on a Sunday afternoon armed with a C90 cassette and actually record those hits of the day for free.

Are you following this? There was a medium that enabled punters to access and store music for free. Yet the music business didn’t fall into the sea, David Bowie didn’t burst into flames and Bryan Adams can still lunch out on how he dominated the charts with a song from a film about some bloke who lived in the forest and robbed people for a living. The world kept turning, people died, babies were born and the cash tills still rang as the music biz still made money. The musicians didn’t complain about radio because they got a royalty rate for every time their song was played, but this royalty rates was negligible and was hardly going to make up for selling an actually single or album, but it was promotion, right? Someone might hear the song on the radio and buy the record.

Everything in the garden was rosey and in the early 1980s the Compact Disc was launched and the music business suddenly sat bolt upright, rubbed its eyes in disbelief as the most amazing idea flashed through its collective brain.

“Fuck me,” the music biz belched, “We can get the punters to buy their record collections again.”

And so it came to pass – the music biz promoted the CD as the ultimate way to hearing music, digital clarity, unbreakable, the perfect music medium – especially as it couldn’t be copied at that time. The marketing machine cranked into life and the record buying public snapped up their copies of Brothers in Arms by Dire Straits, before ditching their vinyl and slowly re-buying their favourite albums which were made for 50p and sold for £14.99. The music biz was the master of the game and realised that you could repackage albums, reissue them, add extra tracks, bonus features and these idiot music fans would spend all their money buying the same product over and over and over again. The music biz liked this – it was good.

Then the Internet came along. In the old days, it was nothing more than a method of sharing text files with each other: electronic mail or e-mail, if you please. When I took my first, faltering steps on the net back in 1995, there was no way of sharing music. I think I managed to download a short music file in 1996, using the computer at work one weekend, and it took something like six hours. And then I had no way of moving said music file home because it wouldn’t fit on a floppy disc (this was before the luxury of CD-R and portable USB drives).

On 7 July 1994, the seeds of change were sowed as the Fraunhofer Society released the very first MP3 encoder though the actual naming convention of the format wasn’t decided upon until a year later. MP3 would soon come to conquer the world, but had to wait for hard drives to increase in size and broadband bandwidth to be able to deliver all this data into the home. By the late 1990s, music fans soon realised that they could encode their favourite CDs to MP3 format and play it back on their home computer. At the same time, the very first portable MP3 players began to hit the market and by 1999, those of us that were tech-savvy had ditched our portable CD players in favour of tiny solid-state MP3 devices.

Then everything changed in October 2001 when Apple released its iPod, which was supported by its iTunes music download service. The implications of this launch were many fold – it offered Joe Public an easy way of consuming music, the record industry could sigh a relief as its artists were now earning cash from downloads and the iPod became the must-have gadget of the early 21st century.

Since then, not a lot has changed. The finger of the music biz has been levelled at file downloaders for killing music, but apparently the converse is true. According to recent figures, those who download music illegally spend on average £70 a year on legitimate music, while those who don’t spend an average of £40. So, the argument is an interesting one. Also, if someone downloads a record illegally, how does this get transformed into a genuine music sale? It’s more than likely that this person, either through choice or economic reasons, would be unlikely to buy the record anyway. So it’s not a lost sale, it’s a non-sale, a sale that never existed in the first place.

This is why I get very annoyed when the music biz compares online illegal downloading to shoplifting. When someone steals something from a shop, a physical product is lost – a physical product that has cost money to produce, to transport and to store. Gone. Pffft. You will never get that money back. However, an illegal download costs the music biz nothing. The thing doesn’t physically exist and so no real product has been lost. This is a phantom theft. The same could be said of those who complain about software piracy. When some software companies sell their products for over £1000 (I’m looking at you Adobe), it’s unlikely that Johnny Downloader is actually going to buy Adobe Web Design CS4 Premium Edition for £1500 if they are a student or unemployed or are just looking to improve their web design skills in the cheapest way possible. I’m not justifying downloading, I’m just saying that you cannot compare it to real theft because the terms are completely wrong.

But I digress…

When the music biz formed, it justified the existence of all those long-haired loser bums who could play three chords on a guitar to call themselves musicians and to aim for a career in the biz. It has to justify itself to exist. If you can play an instrument, then you should have a career in music. Why? Why do the entertainment industries somehow seem to put themselves above every other profession when it comes to importance and money earnt?

Surely a teacher or a nurse is worth more than some guitar wielding wanker? But this entertainment driven society says – no! Entertain me. Keep me from realising that the grim reaper is knocking at the door as you squirt even more fatuous entertainment into my bulging eye sockets and I propel another wannabe pop star or musical star into the spotlight for their regulation fifteen minutes.

And so the true value of music was realised. It was no longer something that could be held up and it’s value pumped up beyond sensibility. It’s just entertainment. It’s just a noise in the background and so the internet says that the value of that noise is 0.044 cents per play. Meanwhile, Bono and his cronies jet around the world several times with a tour that consumes enough power for a small town for a year and then tells us to save the planet, while hiring the best accountants in the business to exploit every loophole in the Irish tax system so that he and his band can embark on some honest tax avoidance, while the rest of us try our best to make ends meet.

To me 0.044 cents appears to be a fair valuation of streaming that tune into my ears. But the artists will complain and the propaganda will circulate that this isn’t a fair amount and the Internet is denying the musicians a true wage. How long does it take to write a hit song? It took Noel Gallagher and Oasis 6-8 hours to record Wonderwall. How much money has that made? How long does it take to educate our children and how much does it cost? Again, it’s got to be worth more than some meaningless three-chord trick penned by an educational subnormal chancer, no?

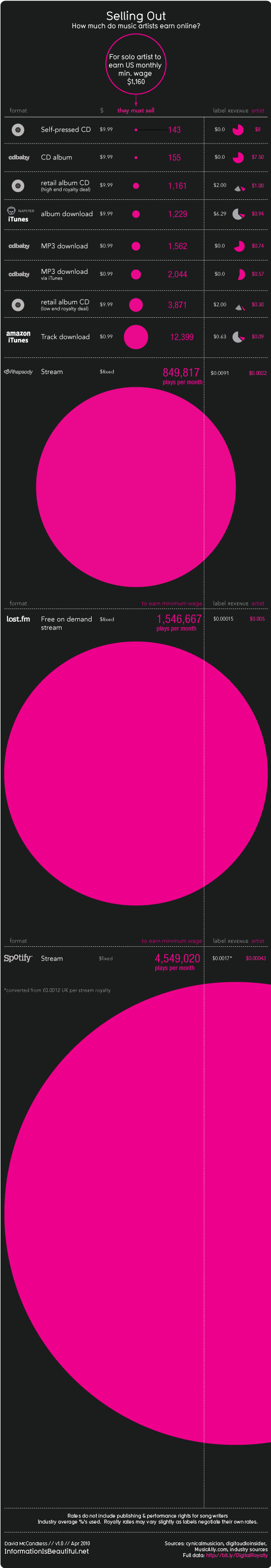

But I got paid 44 cents last month thanks to streaming via Rhapsody and I don’t feel hard done by. And finally a chart to show that being a musician should be a hobby not a profession to moan and whinge and curse about how hard done by you are…

But I read an interview with Brian Eno that echoed my thoughts and general bewilderment about the music industry in which he compared it to those companies that used to run whaling ships during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. They were the captains of their game, and their product lit the lamps of the world, brought light into the homes of many and the by-products of the whale made soaps, corsets and whatever else. Then electricity came along and overnight the whalers were done for. Who needs oil from whales to light the lamps when electricity does the same job without the loss of life? And in a couple of generations the whaling industry was over.

And that’s the music biz, that is…

PS. And now you can watch me do a video performance of this here.